“This mountain was renamed ”Rainier” after a person who never actually set foot on the mountain. It will soon be restored with an ancestral name that matches the name of the people who lived high on the mountain’s slopes for thousands of years – the Ti’Swaq.” Thank you Jane for this update!

Photos by Erica Ellefsen. Go follow her on Instagram!

My stomach was full of butterflies. Our crew was searching the Washington State skyline as we drove south. We spotted Mt. Baker at 3,200 meters (10,700 feet).

Mt. Rainier is over a 1,000 meters (3280 feet) higher than Baker. Where could it be?

Then as we turned the corner, it came into view. A massive mountain of snow and ice. And that’s what we were going to attempt to climb without a guide.

Our group met at Crag X climbing gym in Victoria. We met regularly over the spring to practice crevasse rescue. We had all taken courses taught by guides, but still needed the extra practice to act without hesitation. We also went on other mountaineering trips together, like our adventure up Red Pillar and Shuksan.

That night, we crashed at a car camping spot near the park entrance. (For more info about the logistics of permits and campsite, check the bottom of this post.)

The next morning, we were up before the sun. We pick up our climbing permits, put on our rain jackets and headed off!

I had no idea what to expect for the hike up to Camp Muir. I had read so much about it being a challenging and dangerous place in the winter. I had a hard time picturing what it would be like in the summer.

The first part is on paved trails and is jammed packed with day hikers and families.

Once you get onto the snow, the crowds strangely continued. People love to hike up to Camp Muir as a day trip.

The part of the trip was hours and hours of walking up a gentle snow slope. No ice axe or crampons required.

The views are spectacular. But the sun was just beating down on me. (I do not do well in heat). And the hiking was quite tedious.

Eventually I spotted a structure in the distance.

When I asked the stranger next to me what it was, he said it was Camp Muir.

“We’re there already?!?” I asked.

“It’s at least an hour away,” he said laughing. And he was right. The mountains do weird things to you.

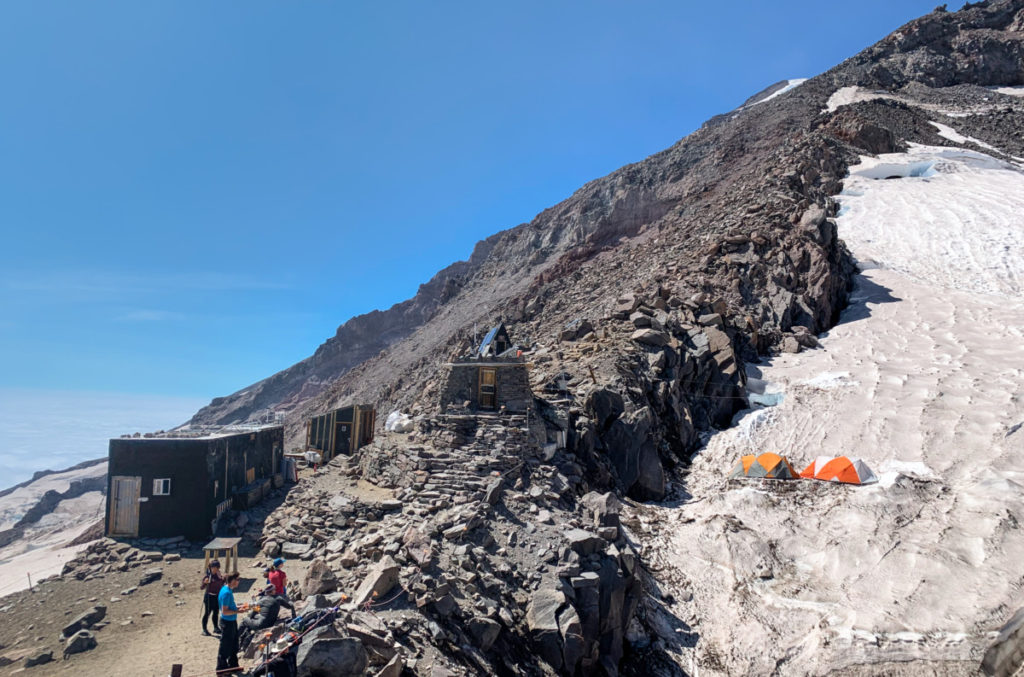

Camp Muir was much smaller than I imagined. I guess that is the power of stories. They can make places seem bigger than they could ever really be.

Walking along the dirt paths, I imagined all the people who had come here before me. I could almost feel the energy.

There was stone public shelter where some 25 or more people could cram together on long, shared bunk beds. I could not imagine planning to stay in there, but it would be life saving in a storm.

On the other side of the camp, there was a private shelter for the guided clients. These clients made up more than half of the climbers on the mountain on our weekend. And there was also a small stone hut for the ranger.

There were public toilets. Half of them were “urinal only.” There seemed to be very few women on the mountain, so perhaps this was fine.

When assembling this Rainier Team, one of my requirements was that our team be at least half woman or non-binary folks. I think were were the only group I spotted that weekend with so few men. Interesting.

We set up our tents on the glacier and got busy with the melting water. We had to melt enough for that day and the next. It takes about 30 minutes to melt 2L of water, which meant many hours of scooping snow into a pot.

Eventually it was time to “go to bed.” We were waking up at 11:00 pm to get on the move by midnight.

Unfortunately a couple arrived right after we all had settled in to bed.

The new comers set up a tent and then very loudly did some … “stuff” in their tent until quite late. Their moans, our nerves and the thin air meant that no one had much rest.

But alpine starts don’t care about noisy neighbours. The alarm went off and we were up!

I started off at the front of the rope team. Midnight was rush hour. We were flanked on either side by groups. You can see the the little clusters of headlamps in the photo below.

Managing my temperature was very difficult. We hiked quickly up some easy terrain and I was sweating. We stopped to strip down to just our base layers. Then we turned the corner and the wind started. We had to stop again to put our layers back on.

The guided groups stopped on Ingraham Flats to have a snack. (Good idea.) We passed them and pressed on to the base of Disappointment Cleaver. (Bad idea.)

We moved quickly through this section because of the seracs. Seracs are large columns of ice, house sized or larger. They are dangerous because they can fall without warning.

It was eery and other worldly to move through this dangerous, oversized terrain in the dark.

Disapointment Cleaver was fairly easy climbing, hiking really.

But the wind. The wind! It pushed me forward and backwards, so forcefully that it almost knocked me off my feet.

The wind whipped dirt into the air and spat it into my eyes, nose and mouth. It went through my two down jackets, my rain jacket, my base layers.

And we had now been going for a few hours with no real break. We needed to eat, but it was hard to find a spot to stop.

Going fast was making us go slow.

At the top of the cleaver, there was nothing by snow and ice as far as you could see. I felt like I had climbed off of planet earth.

The only colours were black and white. You are far away from your friends, walking quietly with your own thoughts. Where were we? What were we even doing here?

At 4,000 meters we came across the one and only ladder.

The ladders are normal household ladders. The guides carry them up there and set them up to make climbing easier for their clients. Folks like us can also use them too.

This setup was quite unique as you had to climb up it. Usually they are put across crevasses, like makeshift bridges. (You’ve probably seen this in Everest movies).

This is the spot I started to not feel very well. My arms were shaking uncontrollably. Was it a fear of the ladder? Or something else?

I don’t have a fear of heights, so I guessed it was hypothermia. I pulled a bar out of my pocket and eat it, hoping the fuel would help my body stay warm.

I tried to open the wrapper but I couldn’t make my hands work. It slipped out of my hands and slid down a crevasse. I would be joining my snack in the crevasse if I didn’t pull myself together.

Not exactly excelling at decision making, I followed my friends up this ladder without complaint.

I walked a few steps more before my legs were also starting to shake uncontrollably. I called out to the team and said I didn’t think I should continue.

My friend turned to me and said he was so glad. Because he had just seen a bus drive by. And he was pretty sure it wasn’t real, but he did see the headlights.

This is when I realized my hypothermia was the least of our problems.

Down we went.

The sun was beginning to rise. I was worried about my friend. I was worried about me.

Eventually I warmed up enough to not feel like I was going to die. I was overcome the beauty of it all.

After a break at the top of Disapointment Cleaver, our friend started feeling a little bit better too. We kept going down.

We all took a long nap at Camp Muir. And I ate a ton of food and drank a lot of water.

Our plan had been to spend a second night up there. But no one wanted to spend hours melting water. Or eating dehydrated food in a bag.

We dreamed of pizza. And sleeping in a hotel. So we packed up and marched right on down that mountain.

Heading down the Muir snowfield was quite challenging. I usually fly down steep snow. But this was bumpy, hard, low angle snow.

We saw day hikers with plastic sleds and plastic bags to slide down. One guy had a snowboard. None of them were moving very fast.

I kept slipping and landing on my behind. But sadly without a sled, I couldn’t slide at all.

At some point on the march I said to Erica, “Do you ever get so tired you aren’t sure if you are awake or sleeping? I might be walking and sleeping.”

She was too tired to respond, but the stranger next to me — out on a day hike with her family — seemed concerned.

We had gone up 2350 meters (7700 ft) and back down the same amount in less than 36 hours. We had slept no more than a few hours

Climbing Rainier was different than I thought it would be.

It had little do with technical skills or route finding. It was more about managing your body’s reactions: to lack of sleep, to lack of oxygen, to lack of warmth. Success depended on whether you made yourself eat even though you didn’t feel hungry. Success was very much a team sport.

It was also way more beautiful than anything I could have ever imagined.

I cannot wait to try it again.

Logistics

Day 1: Before the climb

Attempting this trip in July was challenging as there was so much overlap with car camping folks!

We spent the night at Big Creek Campground. We made the reservations a few weeks ahead of time.

Cougar Rock is closer to where we had to be the next day and would have been a better spot, but it was full when we had tried to reserve a spot.

Day 2: Parking lot to Camp Muir

We got up bright and early to drove to the Paradise Wilderness Information Center to pick up our climbing permit. We had reserved our climbing permit about a month beforehand. It cost $20 to reserve the permit for the group. The permit itself was free.

We each also had to pay a “Climbing Cost Recovery Fee.” This ays for rangers to rescue climbers and helicopters to take poop off the mountain among other things. (This National Park Service site explains what you have to buy very clearly.)

The range checked in with each group and noted when we were going to leave camp. He tried to help us stagger our departure times by at least 15 minutes so there were no bottle necks.

Day 3: Summit attempt

As an unguided group, we were slower than the guided groups. They are just so efficient. I cannot imagine leaving camp later than midnight and still having the time to come down safely.

One of the biggest mistakes we made was climbing too quickly. It caused us to sweat, which then made us cold as we got further along.

We also did not take regular breaks to eat because we didn’t feel hungry. I didn’t know that you don’t actually FEEL hungry at that altitude. You just have to make yourself eat on a regular basis. I’ve now done some research and mountaineers actually set timers to remind themselves to guzzle some meal replacement drink.

Day 3 or 4: Coming back down

We had planned to spend a second night at Camp Muir after our summit attempt.

After this trip, I cannot imagine doing that again. Plodding down the mountain is not so bad and you should have plenty of time left if all goes well.

I’d still make the reservation for the spot on the mountain. But I’d also be prepared to come down.

It took us hours of driving around to find a hotel with any vacancy at all. Campsites were also full. So making alternative arrangements down at sea level ahead of time may also be a good idea for folks climbing in July and August.

Discover more from We Belong Outside

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Climbing Mt. Rainier Without A Guide”

Hi, I just left a comment on your Mt Baket climb. Me and my 4 buddies climbed Rainier on our 3rd attempt in September 2017 with no guide. We had the absolute perfect mountain conditions and it still was the hardest climb I have ever attempted. Good luck on your next attempt !