The Young Peak Ski Traverse is a classic ski traverse in Rogers Pass near Revelstoke. The highest point is 2815m. Lee and I skied 20km that day with 1700m of elevation gain. We stayed in the Wheeler Hut, and I included details about our stay at the end of this post.

Illecillewaet Valley

We started on the Illecillewaet side, leaving the Wheeler Hut around 6:30 am. This is the traditional direction for the traverse, as it provides a gentle climb on the way up and steep skiing on the way down.

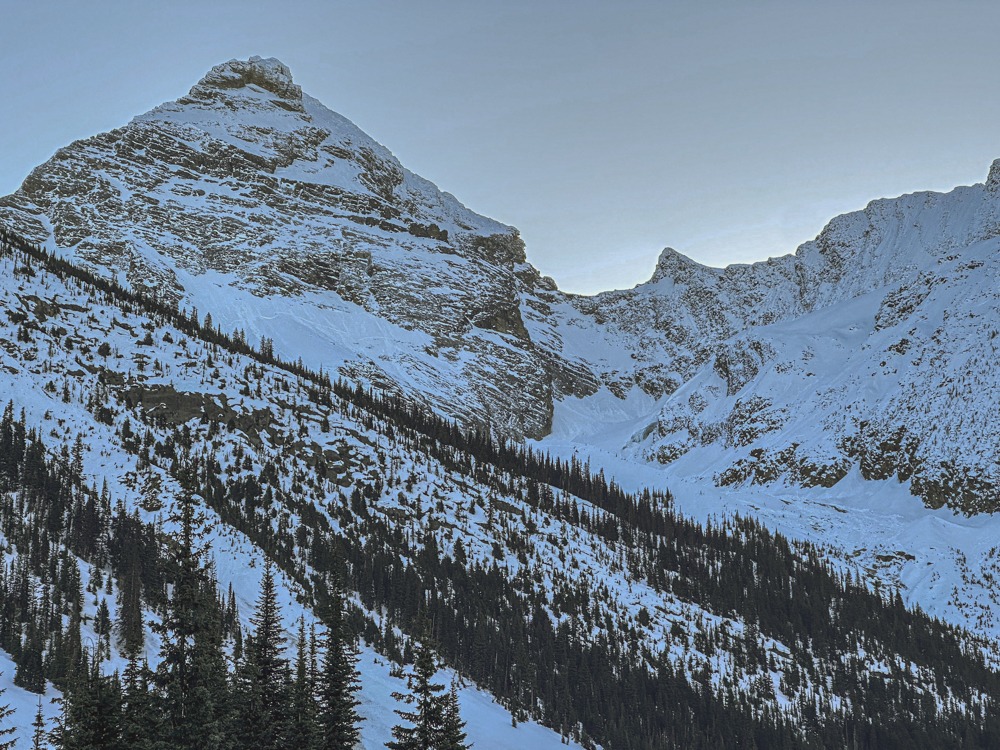

The snow in the valley was very compact early in the morning, which was comforting, given the unsettling amount of avalanche debris we saw. We could not get out of there fast enough, even though everything was still safely frozen in place.

As we approached the moraine, the slope got steeper. The snow started cracking and collapsing underfoot. We were not feeling optimistic about our plans for the day but decided to keep going and see how the glacier looked. We followed the summer hiking trail, but we could have chosen a less steep route to avoid some of our challenges with poor snow.

Illecillewaet Glacier

Once we got on the glacier, things felt much better. The sun was shining. The snow felt firm and stable. We didn’t see any evidence of crevasses. Up we went!

We of course had crevasse rescue gear. We each had a 30-meter rope, as well as materials to build a snow anchor and pulley system. We also practiced crevasse rescue recently. But we decided not to rope up, which is a common way to go in spring skiing. We stayed far apart from each other on the glacier just in case something happened.

The hours spent climbing up a glacier are a strange and special time. It was perfectly silent, not even a bird or plane sound. The sun was beating down on me, making me feel overheated. But the moment I stopped, the biting wind quickly humbled me.

One of the things I thought about on my long, silent slog was how slow I felt. Every few steps, I felt like I had to stop and catch my breath. I knew I wasn’t in the best shape of my life, but this seemed excessive! As soon as I noticed I was having a hard time catching my breath at rest, I realized it was the elevation! You spend quite a long time climbing to 2600m and then stay there for a while. For someone who lives at sea level, this can take a toll on the body.

Summit block

We noticed a steep descent right before the summit block. It was hard to see what was happening over the edge, so we skied down to a lower ledge for a better view. We still couldn’t see what was going on. So we split the difference and kept our skins on but locked in our skis and boots into downhill mode. This was uh… not the best decision.

We ended up cutting underneath the slope, which was the most terrifying moment of the day. It’s hard to tell in this photo, but that tiny blob is me. I am zooming down a very narrow track on the edge of a cliff. Lovely.

The better choice would have been fully transitioning to downhill mode and properly skiing down the steep slope away from the cliff.

After that experience, we felt committed to the traverse. We weren’t going back up there. So onward we went, even though it was getting late in the day. In the spring, it can be more dangerous to travel in the afternoon as the sun has warmed up the snow, possibly making it more avalanche-prone.

The cornice on the summit block was massive. A cornice is snow that has blown around until it sticks to itself, hanging unsupported off the side of the mountain. It’s easy to see from the side, but once you are walking up the mountain, it looks like safe ground. Sometimes people walk on cornices without knowing, and they collapse. (And then you die.) With that in mind, we made a note to stay far away from the north edge.

Looking back at the photos, I realize the summit block wasn’t that steep. We walked up without ice axes or crampons.

But the whole thing felt like quite the mental battle. The wind was howling around us. I was freezing but didn’t want to stop to put on more clothes. The switchbacks were narrow, forcing us to do many kickturns. The cornice creeped me out. It seemed like all the oxygen was gone. It felt like I was battling my way up Everest.

Here is Lee on the final push up the (objectively fairly mellow) summit block.

This was a big deal for me, as it was my first mountain summit since I developed chronic pain and then long covid three years ago. I think the emotional weight of that was a big part of why the summit was so hard for me. (And you know, the wind!!)

Here we are, standing on top at 2815m!

Skiing down Asulkan Glacier and Valley

The skiing off the summit was phenomenal. It’s some of the steeper terrain I have skied at approximately a 40 degree slope. I wish I could have appreciated it more, but I was pretty tired at this point. There was fresh powder, too. What a dream.

We then made our way down, aiming for the Asulkan hut. The folks staying there let us poke around and get out of the sun and wind while we had our belated summit snack.

Going this way limited our avalanche risk given the day’s forecast, but it certainly wasn’t the best skiing. Below the hut was choppy skiing through deep, cement-like snow through the trees. My legs were begging for mercy. But we had to press on.

We had read about the mousetrap, where the path narrowed through a small pass in the towering mountains. This is a dangerous place to linger as any avalanches higher up could run out to the path and bury you. We moved quickly through here.

The last part of the ski out was truly horrendous. I didn’t take any photos as I was so tired and so mad about it. There was a narrow, icy luge track through the forest, as you often see on a ski out.

But this luge track was high above the icy Illecillewaet River. So if you slipped off the narrow ski path, it would be a 10-foot drop onto the rocks and cold water below. I took my skis off and walked a few times, as I did not fancy a swim. And I was losing fine control over my skis as I was so tired.

I read that some groups crossed back and forth across the river several times, often in precarious situations. But we just stayed to the right the whole time and never crossed the river. I think it’s a good reminder to look at the terrain around you and not just follow other people’s tracks (in real life or GPS!)

It was an 11.5-hour trip for us, which I think is acceptable but on the slow side. I personally do not like to have my days go beyond 12 hours. I think most parties come in closer to around 9 hours.

Considering I was housebound this time last year, relearning how to read, write and walk … I chose to celebrate!

Wheeler Hut

Since we were coming from Vancouver, we stayed in A.O. Wheeler hut for three nights. It’s the only place to stay near the road in Glacier National Park.

To book this hut, we stayed up until midnight to reserve our space on the day it opened. We had an earlier signup date than the general public because we were Alpine Club of Canada members.

To park overnight, you need to buy a National Park Pass and pick up a free parking pass from the Rogers Pass Discovery Centre. You can get the parking pass emailed to you ahead of time if you contact them in advance. We didn’t know this early enough, so we had to go to the visitor center in person to pick it up.

The Young Peak Traverse is not in an area of Rogers Pass that requires a winter permit, but if you want to venture elsewhere, it’s worth researching this complex permitting system ahead of time.

The hike or ski into the hut is just over a kilometer from the parking lot. It took us about 20 minutes, loaded down with gear and food. Many people dragged a cheap plastic sled behind them with fancy food and beverages.

The kitchen was fully stocked with countless pots, pans, dishes and mugs. There was even a propane stove! (Pizza anyone?)

The vibe in the hut was quiet and respectful. Most folks were in their 20s or 30s, but there was also a couple with young kids. Everyone was in bed by 9:00 pm, with folks waking up around 5:00 or 6:00 am for ski adventures.

We stored some perishable food outside in our Ursak (bear bag). The first night, mice got in and destroyed everything. I have never had that happen before in a decade of using an Ursak. We left it outside after that to keep the now garbage from smelling up the cabin. The next night, a pine marten tried his hardest to get in. The bag is now covered in teeth-sized holes. It is bear-resistant, so the pine marten didn’t get any food. But the bag looks a bit beat up now. I would not recommend storing food outside in any container, except maybe a hard-sided bear can!

Discover more from We Belong Outside

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.